Laryngoscopy: From Head Mirrors to Fiberoptics, by Reyanna Paul

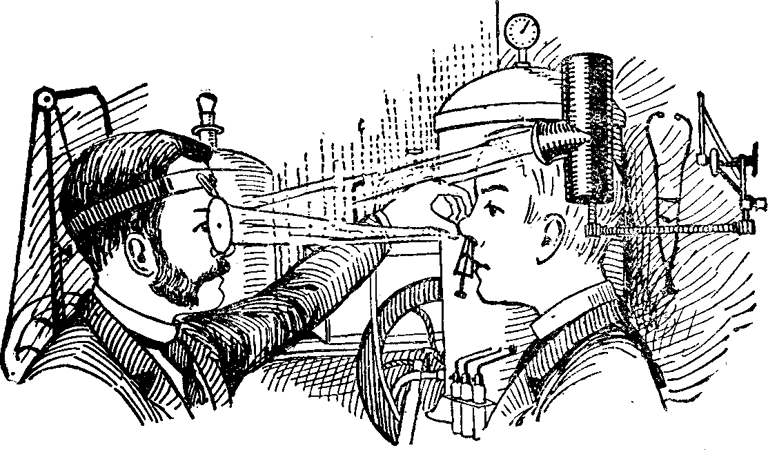

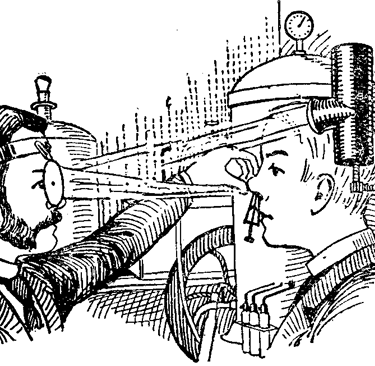

For the episode "Essential Items for your Medical Bag", Inspired to Heal compiled a montage of guests’ responses to the question: “If you could choose one item to put into your medical bag, literal or figurative, what would it be?” Most responses were figurative—but what might the literal contents be? The items in a medical bag evolved over time. The now defunct mirror affixed to a doctor’s forehead, as mentioned in Peter Clarke’s response, is one of the most notable tools that speaks to this evolution. Before modern fiberoptic scopes, doctors relied on mirrors and rigid instruments to see inside the body. As a precursor to the doctor’s forehead mirror, in 1854—Manuel García, a Spanish singing teacher, used a dental mirror and sunlight reflected from a hand mirror to visualize his own vocal cords. His curiosity laid the foundation for the use of mirrors to visualize the throat, also known as laryngoscopy. Johann Czermak modified the process by using a light source concentrated by a concave mirror; thus, avoiding the wait for a sunny day. However, instruments that arose from this observation, like the laryngeal mirror and esophageal specula, required intense lighting and precise angles.

In 1957, Dr. Basil Hirschowitz refined fiberoptic technology and in the spirit of Manuel Garcia, visualized his own vocal cords, and subsequently, a patient’s throat was examined days later. The key innovation was the use of flexible glass fibers, which could transmit light through bends and curves, using the principle of total internal reflection. This principle describes how light travelling through a medium encounters a boundary with a less dense medium and is then reflected back into the original medium. In short, bundles of these fibers carry light into the patient’s body and return a visual image back to the physician’s eyepiece. Hirschowitz used coherent fiber bundles; each fiber stayed in the same relative position from one end to the other, allowing a clear image to form. He, along with physician Larry Curtiss, invented a flexible, steerable endoscope, leading to clearer and more comfortable visualization of the esophagus and stomach—something rigid scopes of the past failed to accomplish. These advances in fiberoptics improved comfort for patients and gave doctors a more detailed view of patients’ internal structures in real time, revolutionizing modern diagnostics and minimally invasive procedures.